J. Jonah Jameson is one of the most famous civilian supporting characters in comics, superhero or others. Thanks to J. K. Simmons’ performance as Jonah in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man movies he has also in some respects become an archetypal character, the embodiment of the major high-powered press editor who’s constantly barking orders to “get pictures of Spider-Man”. And yet, for a character who is so well known and famous, and so widely written about, there’s a major enigma about Jameson as a character. Namely, we don’t know why he was created by Stan Lee and Steve Ditko? There’s also a lack of clarity about what kind of role Jameson plays in the Spider-Man stories. Some have seen Jameson as Spider-Man’s biggest villain, others see him as Spider-Man’s crusty mentor figure? Al Ewing would ask “Or is he both?” I’d argue that Jameson represents an essential function in Spider-Man by embodying the “guilty conscience” of the story. I will argue this based on close reading of selected comics and offering my own reasoning for my interpretation.

Trying to ask questions about the genesis of any part of Spider-Man is extremely hard because of the multiple creative voices, the questionable reliability of many narrators, the lack of information, and in some cases a result of nobody ever asking (in retrospect) the real pertinent questions. For instance, the genesis of Spider-Man was once a straightforward case of Stan Lee claiming to have been inspired by a spider on the wall and most fans taking Lee on face-value as the public face and credited writer on the comics [1]. It’s a story that still persists and gets widely reprinted even if we now know, provably, that this isn’t true [2]. The character of Spider-Man was in some form and shape developed by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby for most of the 1950s with Joe Simon coming up with the “Spiderman” name, and after multiple rejections and failed attempts to make a successful character out of it, Kirby brought it to Stan Lee’s attention during the early ’60s where after an initial attempt by Kirby (who developed the idea of a hero living with his Aunt and Uncle) it was passed on to Steve Ditko who developed the costume [2].

[ASIDE:The question of who should be considered Spider-Man’s true creative author (Lee or Ditko) is one of the great unresolved issues in comics, and something that will be the subject of a later post .]

The point is with Spider-Man, and Marvel comics as a whole, the behind-the-scenes information is sketchy and contradictory. It also doesn’t provide us any real insight into the stories that were finally published. A better approach in my view is close reading. Looking at the comics step-by-step and asking questions and making inferences. This approach will keep us in the realm of reasonable speculation. It will have the advantage of ruling out some questions and ideas, while directing us to more reasonable places to ask questions.

Between Amazing Fantasy #15 (Aug 1962) and Amazing Spider-Man #1 (March 1963)

Regardless of who developed Spider-Man, one thing isn’t in dispute. The character of J. Jonah Jameson who first made his debut in Amazing Spider-Man #1 is indisputably a new creation, i.e. a character who wasn’t featured in Spider-Man’s first appearance in Amazing Fantasy #15. Nor was Jameson featured in any pre-history of Spider-Man in the Kirby/Simon days, nor was he featured in multiple reports of Kirby’s original version of Spider-Man (which simply featured a stocky young man living with his Aunt and Uncle).

Spider-Man made his debut in the pages of Amazing Fantasy #15, an anthology publication that Lee and Ditko had previously worked on and put out multiple short stories. This title was due for cancellation and AF#15 was its final issue. “Spider-Man!” which is the title of the character’s debut appearance and debut story was actually one of four stories in that issue alongside titles like “The Bell-Ringer, The Man in the Mummy’s Case, There Are Martians Among Us”. This issue was published in 1962, putatively August 01, 1962 aka Spider-Man day, which as mentioned before is likely not the case. The success of Amazing Fantasy #15 was enough to convince Marvel’s lead publisher, Martin Goodman, to commission and approve Spider-Man’s own title called The Amazing Spider-Man #1, which came out in March 1963 aka a gap of nearly a year between the character’s first appearance and his first serial publication.

I mention this gap to highlight the weirdness and the unremarked nature of this interim period. The fact is Spider-Man’s first issue appearance, was conceived as a standalone story in the pages of Amazing Fantasy #15 with no expectation for a second issue or follow-up. Whereas his solo title debut, months later, was planned with serialization in mind. The presence of this gap implies that in this interim period, Lee and Ditko had to go to the drawing board and think deeply about what kind of title should Spider-Man be, what kind of stories it should feature, and what kind of characters should the hero meet. And yet having perused multiple books on Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, the period of this gap is never remarked on by either of them, much less asked in terms of the innovations that Amazing Spider-Man as a serial comic brought to the character and world in advance of what was introduced in Amazing Fantasy #15.

When one sees and reads Amazing Fantasy #15 (AF#15) today, it’s often read as a blank to fill-in, a checklist to go over. It’s also read with the later developments of character, so that one reads and assumes that this character automatically developed into the version that followed. Others have argued that Spider-Man emerged fully formed in AF#15 and that later comics hardly build on what’s there but not often citing what elements figured later and when. Not helping matters is that developments that came later are attributed in retrospect to this issue so that the fact the motto “With Great Power Comes Great Responsibility” became prominent in 1987, as mentioned before, is elided when one reads the first issue and finds the closing caption and sees it as a foundational element right from the start.

It’s important to submit Amazing Fantasy #15 to a close-reading, that is to say read the issue as a standalone. Since Spider-Man ultimately became a serial publication which traces its continuity’s start from this issue, this isn’t easy because it would be extremely rare for a reader today to pick up Amazing Fantasy#15 as their first Spider-Man comic, or for that matter their first exposure to Spider-Man. People come to this comic belatedly, after knowing the character from other versions and other avenues. When I say close-reading, I mean read the issue by forgetting everything that came after. And as you are reading asking oneself, what is there in the character’s first issue that is so different from what comes afterwards. With that, one can formulate whether AF#15 could have resulted in a different and alternate form of the character’s continuity.

OBSERVATIONS ABOUT Amazing Fantasy #15

With this reading in mind, here are some observations from reading Amazing Fantasy #15:

- Spider-Man/Peter Parker isn’t a funny character in AF#15. Spider-Man’s debut story is short and it generally features the character by himself but it’s a dramatic and dark story, without any humor or jokes. The character of Spider-Man in comics became known for its humor, and Tom Brevoort in his manifesto, which we discussed before, insisted that “Spider-Man is funny”. AF#15 starts out as a story of a bullied kid being shunned by his peers, reduced to tears by his social rejection, he then discovers his powers and finds a way to monetize it. The closing pages set entirely at night is essentially a noir-crime comic in visuals with dark blues, shadows, and colors. Likewise, AF#15 has what’s called a “downer ending”. If one were asked for the single most famous panel from this comic, it’s likely this image of the hero, unmasked, in tears. So Spider-Man, the hero who cries, is a lot more in keeping with his debut comic than the wise-cracking, joking, version of the character that developed later.

- Spider-Man doesn’t fight any supervillains. This one is obvious but in the character’s debut issue, Peter Parker works as an entertainer and then faces against a burglar. Spider-Man became known for his expansive rogues gallery but none of them are present in his debut story.

- Spider-Man’s thin supporting cast. Previously we covered a census of the Spider-Man cast with most appearances and in the list of Top 10 Most Frequently appearing supporting players, only 2 (Aunt May, Flash Thompson) make their debut in Amazing Fantasy #15 alongside the protagonist. And both characters rank #3 and #5 on the list, in other words their appearance-rate would be surpassed or bettered by characters who appeared afterwards (Jonah, Mary Jane, Robbie Robertson). And those are the only two named characters at that. A blonde girl is retroactively identified to be Liz Allan but she is unnamed in the original and would subsequently drop down in prominence (even in the original run where Steve Ditko and Lee wrote her out of the books by issue #30 and she remained absent in the titles for some 100 issues after that).

- Spider-Man is popular. In AF#15, Spider-Man is a popular TV entertainer when he later developed into a superhero with a controversial reputation. This element wasn’t present in his debut issue.

SUMMARY OF THE INTERIM PERIOD

Based on my observations, you can argue that the character of Spider-Man were he truly in line with how he first appeared in Amazing Fantasy#15 should be the story of a very serious, very lonely, young boy who was only ever popular as his alter-ego Spiderman [the hyphen is far from consistently applied in the original issue] but was otherwise friendless and whose only family left was his Aunt whom he made into a widow. The only contrast to this, would be his successful showbiz career as a TV performer, which we are not informed at the end of his debut issue is something he’s leaving (more on this later).

It would also be a comic with touches of horror and crime since the closing pages features gritty settings like an abandoned warehouse where Ditko’s drawings by emphasizing on Spider-Man as a grief-enraged hero almost frames the Burglar as a sympathetic victim to a monster. It’s possible to take these panels out of context and convert it into a slasher story of a strange masked man cornering an ordinary man armed with a gun. “Friendly Neighborhood Spider-Man” neither of the first two adjectives or adjective nouns apply to the version in Amazing Fantasy #15.

Which brings us back to the interim period between AF#15 and ASM#1. During this gap, either Ditko and/or Stan Lee must have had discussions or ruminations about how to convert Spider-Man from a standalone story and character into a serialized story. In TV terms, AF#15 is the Pilot, while Amazing Spider-Man is the greenlit TV Show. In any long-running TV show, the opening episode tends to be somewhat self-contained and standalone whereas more serialized elements are introduced in the second or third episode. However as a rule, when a Pilot gets the go-order, the TV executives either re-edit or re-shoot the Pilot to better align it with the serial show that follows, whereas in the case of comics, his “pilot” – AF#15 – was published and released, and several months later we got the full TV show which meant that neither Lee nor Ditko could go back and make AF#15 more aligned with the version of the character they later serialized.

The significance of this gap, and the fact that it’s little covered and remarked on, and which to my knowledge, neither Stan Lee nor Steve Ditko were ever asked about, or induced to reflect on strikes me as a major failure of comics’ scholarship. It’s the most fundamental question about the creative process but decades of publicity, fan-worship, industry scuttlebutt, and the general ephemerality of comics as a medium, buried it completely.

As such if we are to understand the basic question about how Spider-Man became a major comics figure and the foundation for the only major Marvel character to remain consistently popular and successful in sales and readership over six decades, rather than base our knowledge on the nuts-and-bolts of storytelling, we instead have to rely on the dime store philosophy of various eras. Much of which usually devoted to variations of “Spider-Man is About Youth” which do not begin to provide a satisfactory answer.

In my opinion, understanding how Spider-Man became a successful serialized entity revolves on two questions, both of them have an answer that comes from the same place, if not being the exact same answer. They are:

- Given the serious nature of the story and the gritty nature of the character as a crime-fighter in AF#15, why was the decision made to turn the ongoing title into one with a significant comic and comedic tone, with a more light-hearted version of the character?

- What was the idea behind the creation of J. Jonah Jameson? What role and function does he exist to perform for Spider-Man as a whole?

ENTER JONAH

In March 1963, Amazing Spider-Man #1 was published and Stan Lee and Steve Ditko would start a run from March 1963 to July 1966, that includes 38 issues and 2 annuals. The interesting thing to observe about Amazing Spider-Man‘s very early issues is that you can see the writer-artist team adjusting to converting from anthology writers to a single issue. So for instance, ASM#1 and ASM#2 have two comics stories, one being 14 pages, and another being 10 pages. The issues after that were generally 21 pages full-length issues each. This technical detail signifies that converting from anthology to single issues was a process of adjustment not only in story construction but also in terms of writing and pacing.

In Amazing Spider-Man #1 there are two stories, one of which strangely enough reuses the title of AF#15 – “Spider-Man” and the other is simply titled “Spider-Man Vs. the Chameleon”. The latter story (10 pages) features the Fantastic Four and Chameleon, the first real supervillain introduced in the story. In other words, it’s the shorter of the two stories that actually reads most like a traditional superhero comic whereas the first story (14 Pages) which is divided into three subsections titled “Part 1″/”Part 2″/”Part 3” is more character-driven.

The first page of ASM#1 features a splash image of Spider-Man surrounded by a mob all pointing their fingers to him. Bold letters call out “Freak!” and “Public Menace!”. One among the mob is foregrounded.

Poking out of a bush of fingers and raised fists is the left profile of J. Jonah Jameson. He’s there in the first page of Amazing Spider-Man #1.

In other words, J. Jonah Jameson is the first entirely new and original element added to Spider-Man after AF#15. We see him on the first page of the solo ongoing issue. Equally interesting is that the splash image communicates an entirely new idea – Spider-Man is seen by the public as a menace. As established above, in AF#15, we know that Spider-Man was a popular entertainer on TV. So somehow for his first solo issue, the decision was taken by Lee and/or Ditko to make Spider-Man’s public reputation be a menace. This is an entirely new and innovative element to the character. Not inherent to the foundation of AF#15 in any respect. In fact it’s the complete opposite. In AF#15, Spider-Man is loved as a TV performer but he’s hated as Peter Parker in school. Here we see on the first page of ASM#1 that Spider-Man is accused of being a “Public Menace” and “Freak” right away.

The first pages of ASM#1 offers a quick recap of the events of AF#15. We see that Aunt May, widowed on account of Ben’s death, is worried about her difficulties over paying rent. Peter out of guilt and regret is motivated to trying to make money and so he returns to show-business in Page 4, with a panel that looks like it could have featured in AF#15’s panel-montage of Spider-Man’s fame.

Then we get a small scene where Spider-Man collects a check but cannot give his real name out of a desire to preserve his identity so the manager gives it to “Spiderman” but then Peter goes to the bank and the teller informs him that he cannot accept a check in the name of “Spiderman” [hyphen not yet consistently applied] owing to the impossibility of verifying identity.

In the same page, there’s a panel shift to Jonah Jameson on his desk and this is in fact Jameson’s first true appearance in Spider-Man. This panel here. The panel right after this has the show’s manager inform Spider-Man that he’s not in demand anymore owing to his reputation being clobbered by Jameson. We see the headlines on the newspaper handed to him “Spiderman Menace” and then we get several panels of Jameson giving media talks about Spider-Man being a “masked menace” and starting a scare panic against Spider-Man.

We see Peter Parker lament to a newspaper vendor about how Spider-Man is hated compared to the Fantastic Four (which incidentally is the first acknowledgment of the Marvel shared universe in Spider-Man comics). Then the story is revealed that Jameson’s son John Jameson the astronaut (Not a helpful man when it comes to naming his children, our Jonah) is about to take a test rocket. Peter attends it, and the rocket flight malfunctions leading to Peter to decide to intervene as Spider-Man and this results in the first face-to-face encounter between Spider-Man and Jameson.

Jameson even after knowing that Spider-Man alone can save his son’s life, proceeds to insult him to his face, and Spider-Man rushes in anyway. Then after succeeding, Peter reads the newspaper and finds out that Jameson still calls him a menace with his public reputation ruined for good.

The follow-up story “Spider-Man vs. the Chameleon” has the Chameleon pose as Spider-Man and commit crimes while the real Spider-Man tries and fails to join the Fantastic Four who have a polarizing response to him, with Ben Grimm especially seeming to take the negative press on Spider-Man to heart.

OBSERVATIONS ABOUT Amazing Spider-Man#1

Obviously the big theme in both stories of ASM#1 is that Spider-Man experiences “reputational damage” as we call it today. Jameson goes on talk shows and the press circuit and brands Spider-Man as a “menace” and the bad press Spider-Man has accrued has led the Fantastic Four to have a negative impression of him which is compounded by Spider-Man’s try-hard attempts to inveigle himself into the Fantastic Four for money. The result is that the character who was publicly liked in AF#15 is now unpopular and that there are people who dislike and mistrust him so much that no single grand gesture i.e. saving his son from a rocket, can win them over.

The presentation of these events is likewise very different. For instance throughout ASM#1 although Spider-Man experiences misfortune as a character it’s not treated the same way as in AF#15 which played Peter’s rejection straight as melodramatic and upsetting. The only bits of seriousness in this comic is Peter’s guilt and contrite nature at seeing his Aunt struggle to pay the rent. Whereas Peter’s own struggle to cash the check in the bank is essentially a satirical gag. Jameson’s over-the-top description of Spider-Man as a threat and his blinkered petty dislike of Spider-Man is so unfair that it crosses the line. This is further heightened by the fact that in the second story, Ben Grimm/The Thing, the most popular of the Fantastic Four reads the papers and accepts the negative view on Spider-Man. In other words, Jameson is aligned with Ben Grimm in their approach to Spider-Man in ASM#1 which signifies that Jameson as a character is not exactly a villain even if he plays an antagonistic role in the first issue. If Jameson was intended as a purely villainous figure it would be a very odd choice to align him with the most popular character of the Fantastic Four.

There’s a difference between Flash Thompson and Peter’s classmates insulting Peter for being bookish and uncool in Amazing Fantasy #15, and bullying him to tears, and someone like Jameson who attacks Spider-Man because he wears a mask and he’s unknown and cannot be trusted. The former is the kind of cruelty that is very accessible to everyday experiences, especially of those who like to read comics (at least until the last 2 decades before social media and culture legitimated comics readers to bully and harass others online). Whereas Jameson’s dislike for Spider-Man is baroque and remote from reality. In the sense that the idea of someone using superpowers and putting a brightly colored costume and being misunderstood and personally targeted by a newsmedia personality while it’s open to all kinds of symbolic and allegorical poking of sticks, is fundamentally remote and alien from everyday lived experiences. That means that Jameson’s dislike of Spider-Man creates dramatic conflict without having dramatic importance, which allows Jameson to inhabit the gray area of the “love-to-hate”/”hate-to-love” characters.

From a certain perspective, i.e. to someone who doesn’t know or have access to Spider-Man’s thoughts the way a reader does, Jameson’s skepticism to someone wearing a mask and pulling stunts would be reasonable. As would his distrust and skepticism at the concept of a TV entertainer volunteering himself into a rescue operation that NASA seems clueless about. It gets bizarre of course when Jameson continues to dislike Spider-Man after he behaves selflessly and at which point it doesn’t especially seem reasonable, and Jameson at times seems like a cross between a curmudgeon boss and loud guy on subway preaching nonsense.

Jameson as a character achieves three things on his entry into the narrative:

- He overturns the status-quo and makes Spider-Man unpopular and distrusted. He makes it so Spider-Man can’t work in show-business again which compounded with the death of Uncle Ben as family breadwinner means that Peter has to seek out alternative ways to find money and that in the second issue will lead to Peter selling photos of Spider-Man to Jameson himself.

- He introduces a comedic and satirical element into what started out as a dark comic. As a character Jameson also changes the tone of the stories completely. Because he’s a comical foil, against whom Spider-Man’s struggles can’t be resolved by means of force or through any big grand gesture of heroism. This provides a complex social context in the superhero world of Spider-Man while also providing for tonal variety and shifts from the serious world of AF#15.

- He generates situations that provides a chance for Peter to prove his moral growth to the reader. Jameson establishes that simple grand gestures aren’t enough to gain fame and public approval and this introduces the concept that being a superhero isn’t simply about “good deeds” or that doing “good deeds” wouldn’t carry an intrinsic reward. As such Jameson allows Spider-Man to become truly selfless, driving Peter to do good without any guarantee or promise of reward.

This concept is driven home where during the shuttle flight disaster, Peter hops in as Spider-Man because he’s the only one who can save the astronaut and that this is the first decision in Spider-Man’s publication history which is purely selfless.

In Amazing Fantasy #15, when Peter went after the burglar he was driven by personal revenge, his attempts before at making money as a show-business performer, and earlier in ASM#1 it’s driven out of guilt and concern for his widowed Aunt. When Spider-Man rushes in to save John Jameson, he’s doing it for some random stranger, the son of the man who is smearing his reputation, and he leaps in because he can. In Spider-Man’s defining action in Amazing Fantasy #15, he did nothing as a burglar passed him down a hallway into an elevator, in his first solo-issue, we see Spider-Man leap into action right away when he could have stayed back and claimed that helping astronauts is NASA’s job.

Having seen the character behave so selfishly in AF#15 and at the start of ASM#1, it makes Peter’s actual turn to selflessness much more endearing especially when we see how little he’s rewarded for it. And since Jameson is the cause for Spider-Man’s lack of reward, he is indirectly the cause of Spider-Man’s turn to true heroism, the gauge by which readers measure the moral good of Peter Parker.

UNMOTIVATED DISLIKE

Yet there’s still one basic problem. Jonah’s dislike for Spider-Man doesn’t make much or any sense. It seems essentially unmotivated.

Over the years various writers have provided a series of motivations for Jonah’s dislike for Spider-Man, and while some seem more plausible than others, they are all in my opinion skirting the true problem [3]. Some have argued that Jonah dislikes Spider-Man because he lost faith in those who wear masks because a mugger attacked his wife. Some have tried to argue Jameson dislikes superheroes because he likes to stand up for the normal civilians but as Peter points out in ASM#1, Spider-Man is disliked where the Fantastic Four are embraced (although again this has also been inconsistently applied by later writers who show Jameson antagonistic to other Marvel heroes). Jameson’s supposed hostility to superheroes or super-powered people wouldn’t prevent him from later funding the project that resulted in the development of the supervillain Scorpion. To complicate all this, Lee-Ditko themselves gave motivations for Jameson that are contradictory and don’t really make a great deal of sense.

The real problem is that Jameson calls Spider-Man a “Public Menace” before he becomes a major superhero, before he starts actively pursuing and fighting criminals, before he does anything that might provoke enough of an ambiguous response to be labelled a “public menace” (i.e. collateral damage from fighting supervillains):

- ASM#1 establishes that Spider-Man was a showman on TV at the start, and it’s odd, some would say extreme (though not completely unrealistic), to call someone a “public menace” simply for appearing as a TV entertainer.

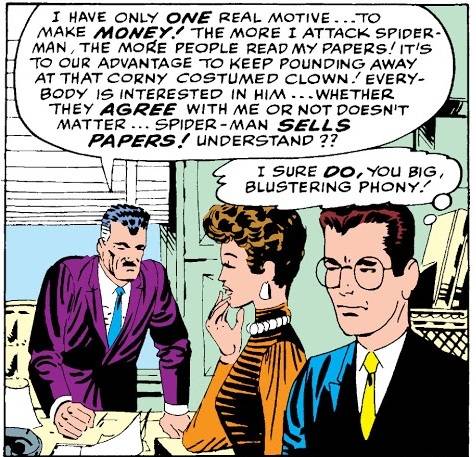

- In Amazing Spider-Man#5, when Jameson is asked by Peter and Betty why he’s attacking Spider-Man, he says that he’s doing it for the money and attacking Spider-Man gets publicity and revenue. The problem is Jameson as a prominent media editor and personality is clearly a wealthy man and Spider-Man is a recent and very new celebrity, and also very popular. Attacking Spider-Man at the outset is a controversial move and doesn’t exactly make financial sense at the start. Notably Peter Parker’s own thought bubbles in response to this claim is to label Jonah a “big, blustering phony” with Ditko drawing a half-sneer and curled lip on Peter’s face to indicate doubt and contempt at this.

- Even more controversially, in Amazing Spider-Man #10 by Lee and Ditko, we have a scene showing Jameson introspect on why he dislikes Spider-Man. In this panel, Jameson claims that he’s jealous of Spider-Man and that he seeks to tear him down because he can’t accept someone like him being braver than him, a man who spends all his life in pursuit of money. The resentment of a news publisher wanting to bring down someone out of his moral inferiority appears to echo ideas of Ayn Rand, for example the architecture critic Toohey from The Fountainhead who hates the hero Roark so much he seeks to tear him down [4]. The fact that Steve Ditko became known for espousing Objectivist ideas later in his career lends this credibility. So some see Ditko’s version of Jameson as determined by his objectivist ideas while the more charismatic and nuanced portrayal (presumably by Lee and later writers) overturned this conception [5]. However, as Blake Bell revealed in his biography of Steve Ditko, Stan Lee was also an admirer of Ayn Rand and it was Lee who suggested Rand as reading material to Ditko [6]. Stan Lee of course wrote the dialogues (albeit at Ditko’s directions and marginal notes). In addition Abraham Riesman’s recent biography of Lee confirmed that he censored a Fantastic Four comic where Jack Kirby wanted to parody and spoof objectivism [7]. In other words, the biographical record for the meaning of this motivation and attributing objectivist ideas to either Ditko or Lee solely, is extremely difficult.

In either case, even the objectivist coding and idea doesn’t make sense as motivation. The problem with this “motivation”, even voiced by its creators, is that Jameson says this before Spider-Man acts altruistically when he’s a TV entertainer who hadn’t yet dove in and saved his son heroically. In the same way Jameson calling a TV-Entertainer a public menace is extreme, him seeing Spider-Man, in his “Instagram Influencer” days, as someone to tear down feels like going too far in the other direction. What reason would Jameson have in ASM#1 for going after Spiderman when he only knows him as a TV performer who has done nothing to merit any resentment? Even from an objectivist perspective, how would tearing down a TV celebrity who has shown no courage vindicate how Jameson feels about himself?

- Chip Zdarsky in his story “My Dinner with Jonah” (Peter Parker: The Spectacular Spider-Man #6 published in November 2017) introduces a “retcon” that Jameson was in the TV audience during Spider-Man’s early days as a TV performer and that Jameson’s impression of Spider-Man stemmed from the very early pre-superhero days of Peter Parker. Retcons in general, i.e. continuity explanations developed years, in this case decades, to fill in the blanks are often maligned. But this one, which inserts Jameson into the background audience of the pages of Amazing Fantasy #15 feels plausible. It adds to our understanding without changing anything fundamental of the characters and their relationships, and it also feels like the kind of change Ditko and Lee would have planned were they able to serialize right away from AF#15 and ASM#1 without the big gap. Yet this explanation still doesn’t explain why Jameson mounted a smear campaign because Zdarsky has Jameson exclaim “You were a great performer!” and that “You’re an entertainer and you should have stayed that way” but as we have seen from reading ASM#1, the person responsible for ending Peter’s career as entertainer was Jameson himself. He called a TV performer a “Freak” and “Public Menace” when he was still on TV and not catching any thieves like flies.

Jameson’s character motivations doesn’t make sense from a storytelling point of view but he is essential on a deeper sense, on the level of subtext. Jameson externalizes the thematic conflict of Spider-Man by essentially serving as Spider-Man’s guilty conscience. Indirectly, it was Jameson who pushed Peter to become a selfless superhero and who also through his antagonism proved to the readers that Spider-Man had become selfless. And he did that by disliking and distrusting Spider-Man before he had done anything.

GUILTY CONSCIENCE

Now let’s assume you are the original reader of Spider-Man, i.e. you picked comics of the stands in 1962 and 1963. You read Amazing Fantasy#15 and then you see the first page of ASM#1. The first page paints Spider-Man as a “Freak!” and “Public Menace!” Now you had read AF#15 several times and dog-eared your issue of AF#15 so you remember that story well. But now you read ASM#1 and you wonder why is a popular entertainer established in AF#15 suddenly painted as a freak? You ask “Why do people hate Spider-Man” all of a sudden.

Now if you pause at this page and come up with a logical explanation or guess at what the reason is, then you you might conclude

- “Oh they figured out that Spiderman let the burglar go who killed the uncle”. That might be it, right? Based on the evidence we see in Amazing Fantasy #15 it’s not unlikely at all for people in-universe to connect the burglar who raided the studio with the one caught in the warehouse fleeing the police after he shot Ben Parker.

- You also think Amazing Fantasy #15 was a sad story and a dark story with a tragic ending. Spider-Man being exposed for letting that burglar go would be in keeping with that comic’s themes.

These explanations are both plausible based on what was previously established and then you turn over and read the comic and Lee and Ditko suddenly destroyed your theories because ASM#1 is a different and much more light-hearted comic than AF#15 and Jameson’s reasons for disliking Spider-Man aren’t premised on the reasonable foundation that the character’s act of indifference led to the death of an innocent man leaving behind a broken family. So the result as a reader is that Jameson has irrational reasons for disliking Spider-Man and calling him a “public menace” and at the same time, unknown to him, there exists believable reasons why he should hold Spider-Man to account.

There’s a weird kind of character dynamic that I have observed in superhero comics, serialized superhero comics, that I like to call the “Guilty Conscience”. It’s essentially a character archetype who represents the unspoken and unstated subtext of the stories, but this subtext is displaced and externalized on to a third party. Usually this is an antagonist (in the two other prominent examples, which I will explore soon, they are villains) but in Jameson’s case it’s a regular supporting character and comedic foil. On the level of subtext, Jameson externalizes the moral lessons of Amazing Fantasy#15. As wrong and unfair as Jameson is in calling Spiderman a menace and scapegoating his character, on a deeper level Jameson reminds the reader that there was a time when Spiderman was indeed a ‘public menace’ when his inaction led a burglar to kill an innocent man.

Likewise Lee and Ditko wish to make Spider-Man a superhero character and adventure hero, and not exactly a character in a realistic story. AF#15 is as close as Spider-Man gets to realism, in terms of psychology and verisimilitude, because aside from the unreal element of super-powers via the spider-bite everything else in that comic is in the realm of the plausible. Amazing Spider-Man #1, on the other hand, features rocket launches in New York State, allusions to the Fantastic Four in the shared continuity and the second story has Peter meeting the Fantastic Four superteam while also dealing with a supervillain who can change his face. ASM#1 is absolutely an adventure story but it still retains story and character texture from AF#15. The dichotomy of Spider-Man is that he has shades and layers of psychology while also being a serialized adventure hero whose adventures are essentially independent of psychological considerations.

Imagine if there were no J. Jonah Jameson in Amazing Spider-Man #1.

- Peter Parker would likely still struggle to cash checks made out to “Spiderman” but he would still be in demand as a performer.

- The rocket launch might not feature Jameson’s astronaut son but it’s likely that the rocket launch still happens (since Jameson’s son doesn’t seem to be a scientist-administrator in charge of the rocket and its location in NYS) and another astronaut takes his place and Peter attends this event owing to his science interests.

- The rocket malfunctions and Spider-Man saves the day. Without Jameson, he’s praised as a hero and seen positively and the Fantastic Four while still turning him down for his attempts to join them are more encouraging and helpful.

Without Jameson, the plot of ASM#1 can still be the same since he’s a supporting character and not an antagonist, but what is lost is the texture, context and moral dilemmas, i.e. the emotional center which is what supporting characters provide. As a character, Jameson instills emotional conflict and shades of layers into the characters and not just himself but also in Peter. Without Jameson, we dilute the selflessness of Peter rushing in to save the rocket of the son of the man who smeared him. It feels like typical superhero stuff and not a character-action specific to an individual. Without Jameson, we also get Spider-Man as a superhero adventure without any satirical and comedic spirit. We also get a sense that without Jameson, Spider-Man is a hero who is loved for a single grand gesture and attains a measure of redemption when in fact the framework of AF#15 is that Peter won’t forgive himself for his inaction and that the moral is that Spider-Man should act on behalf of others, even those who he doesn’t care for, and in the case of Jameson, those who dislike him.

So as a character Jameson represents, unwittingly to him, and unknowingly to the reader, the character and story’s “guilty conscience” who ensures that somehow Spider-Man will always be tested morally and proven selfless in the eyes of the readers but not necessarily in the wider Marvel world.

One interesting element in Peter’s internal monologue at the start of ASM#1 is that when he confronts his woes about Aunt May’s struggles to pay the monthly rent, Peter (very briefly) contemplates using his powers to rob stores. One panel later he talks himself out of it but as a reader, well before Jameson’s smear campaign reaches anywhere, we have a glimpse that Peter’s thought processes briefly fantasized about robbing places (in the same way most people at some point or another might or might not have weird fantasies here and there).

So while Jameson’s inaccurate about Spider-Man’s actions, he very nearly guesses at aspects of Spider-Man’s thoughts, namely that Peter has thought about robbing banks and is in desperate enough conditions that would drive or would have driven most anyone to small schemes here and there. In a realistic story and setting, perhaps Peter as a teenager in order to provide for his widowed Aunt might turn to drug dealing as a struggling teenager or given his aptitude for chemistry might turn into a teenage high-school Walter White (whose associate Jesse Pinkman is a high school teenager after all, though from a well-off family unlike Peter).

The addition of Jameson as a moral agent and the personal nature of a grudge lends a melodramatic touch because Spider-Man acting in a selfish way would in turn prove Jameson right, and a reader is primed in this issue to not want Jameson to be proven right about Spider-Man.

In this way, the serialized narrative of Spider-Man is set with Peter on a quest to prove and maintain his conscience in a world that doubts his, who is constantly set to earn and maintain trust because he cannot count on grand gestures or single acts of redemption because there are those with long memories who will dredge up the past. Jameson provided the engine for Lee and Ditko to convert the moral dilemma of AF#15 into an ongoing perpetual motion story which can be episodic and continuous. The stories aren’t about villains being defeated or about “ending crime” a la Batman, rather it’s about the hero maintaining his conscience, situating himself in a world where acts of conscience are often invisible and unrewarded. It’s nothing for Superman to save Jimmy Olsen and Perry White and Lois Lane, all of whom are his pals and supporters. But it’s quite something when we see Spider-Man rush in to defend those who dislike him or oppose him such as Jonah and Flash Thompson.

In other words, Spider-Man is about maturity, about leaving behind youthful grudges and petty self-righteousness. It’s about growth as David Mann pointed out, since we see that in just his second published story, Spider-Man slowly grows and develops with his original creators not at all satisfied with simply repeating the beats of AF#15 [9].

CONCLUSION

This is the first I’ve written of Jameson but it absolutely will not be the last. There’s so much more one can say about Jameson that hasn’t been said either here or elsewhere. Much more to say about the way writers and others have interpreted the character in later runs, sometimes interesting sometimes not. There will be a follow-up shorter post where I cover some stuff I didn’t have time to get here with my close-reading of the very early Spider-Man stories.

J. Jonah Jameson is one of Spider-Man’s two most important supporting characters, making nearly as many appearances as Mary Jane Watson and while Mary Jane has the stronger claim to being the co-lead of the Spider-Man stories, Jameson is still a deeply important character in the comics. He stands as proof on the value of a civilian supporting cast in a superhero adventure story, someone who enriches and deepens the story and makes the protagonist into a deeper character. He also stands for the human element that life is full of grays since Jameson was an immediately popular character with readers (winning the 1960s fan Alley Awards as “Best Supporting Character” twice) despite all his unlikable traits [8]. There was something strangely endearing about Jameson.

Jameson provided the Spider-Man comics with personality, character, and identity, and as the first entirely new character and new element on Spider-Man he had a bigger immediate impact on the long-term development of Spider-Man in terms of bringing in humor, moral conflict, and complexity than even the origin in Amazing Fantasy #15 did.

SOURCES

- Stan Lee and Steve Ditko. Marvel Masterworks: Amazing Spider-Man Vol.1. (Includes Amazing Fantasy #15 and Amazing Spider-Man 01-10). Published in September 2003.

- Chip Zdarsky and others. Peter Parker: The Spectacular Spider-Man Vol. 1 – Into the Twilight (includes issues #1-6). December 2017.

REFERENCES

- “Stan Lee Originally Considered Naming Spider-Man After a Different Bug”

July 25, 2021. Screenrant. https://screenrant.com/spider-man-stan-lee-original-name-fly-inspiration/ - “Lee & Kirby & Simon & Ditko & Oleck: The Spider and the Fly.” The Tom Brevoort Experience. October 24, 2020.

https://tombrevoort.com/2020/10/24/lee-kirby-simon-ditko-oleck-the-spider-and-the-fly/ - “Why does J. Jonah Jameson hate Spider-Man”. Brian Cronin. CBR. July 07,2019. https://www.cbr.com/spider-man-j-jonah-jameson-hatred-reason/

- “Spider-Man Shrugged: The Lack of Randian Heroes in The Amazing Spider-Man”. Desmond White. Sequart. 3 May 2014.

http://sequart.org/magazine/42384/the-lack-of-ditkos-objectivist-bias-in-amazing-spider-man/ - “Thoughts on J. Jonah Jameson as a Character”. Steven Attewell. Race For the Iron Throne (Tumblr). September 20, 2018.

https://racefortheironthrone.tumblr.com/post/178291615356/thoughts-on-j-jonah-jameson-as-a-character - Strange & Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko. Blake Bell. Page 86.

- “True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee”. Abraham Riesman. Published in 2021. Page 157.

- Jameson won “Best Male Normal Supporting Character” twice in 1967 and 1968 in the now defunct “Alley Awards”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alley_Award - “Spider-Man Was Never Just A ‘Loveable Loser’” by David Mann. Sequart. Fri, 2 May 2014.

http://sequart.org/magazine/42314/spider-man-was-never-just-the-%3C!–e2–%3E80%9cloveable-loser%3C!–e2–%3E80%9d/