Here’s a fundamental question to ask with the development of Spider-Man? How is it that the most famous superhero to originate as a teenager, was developed by two men who never knew the word “teenager” even when they were teenagers? Where, when, and at what stage did the concept of “the teenager” enter into the development of the character? This post will explore Spider-Man’s development step-by-step and trace the decision-making that led to the conceptualization of Spider-Man introduced as a teenager. It will measure this against the history of comics in the 1940s and 1950s, and also take into account the biographical facts of its creators and the historical-cultural forces active in that time. The post you are about to read is grounded in the (currently) available biographical facts of Spider-Man‘s creators as well as close reading of the comics. However, it’s also mixed with amateur sociology (with citations) and speculation, so I do not pretend to be objective or offer anything other than my own guesswork below.

As we established before, Spider-Man as a character and concept which is to say a superhero with spider abilities or insect themes, as well as the name “Spiderman” did not originate overnight in 1962. We now know provably and demonstrably that Spider-Man as a concept was nearly a decade in development by Jack Kirby and Joe Simon [1].

It’s one of the big, fundamental questions that lies at the heart of the origin-myth of perhaps Marvel Comics’ most popular single character…how much did Jack Kirby have to do with the development of Spider-Man, and how much of the final product was based on his ideas. As is typical in these instances, I think the actual answer amounts to: Jack was definitely involved, and Spider-Man would not have existed without his involvement. But I also think the version of the character that was published owed relatively little to his conception and what he put forward–even though it was ultimately derived from those ideas.

Tom Brevoort, “Lee & Kirby & Simon & Ditko & Oleck: The Spider and the Fly”

It was Joe Simon who seemed to have developed the name Spiderman and he even designed an early version of a logo as you can see on top of this post. Kirby and Simon tried constantly to make the character and concept work but found their concept rejected, which led them to make retools as well as sponsor spinoffs by other artists and writers at the Simon and Kirby studio, such as The Fly. By the end of the 1950s, Jack Kirby was on a loose end and arrived at Atlas Comics, the company originally founded as Timely and would later be renamed as Marvel. Kirby and Simon had worked at Timely in the late 30s and early 40s where they created Captain America.

JACK KIRBY’S SPIDERMAN

After he returned to Timely/Atlas, Kirby initially began work on monster comics and then eventually he and Lee developed Fantastic Four under the Marvel Method. At some point, we don’t know when, Kirby decided to dust off his rejected “Spiderman” idea and developed a few pages as proof-of-concept. In the late-1950s, the Simon and Kirby studio faced financial difficulties and had to close-shop, and the two founders divided assets and parted ways. Kirby got to keep the “Spiderman” concept and logo and as such had access to it when he arrived at Marvel [1].

At some point early on, either after FANTASTIC FOUR had proven to be an immediate hit or even before, Kirby continued to pepper Lee with ideas, and many of these grew out of the material he had developed with Joe Simon but had never reached fruition. It’s impossible to say for certain which man hit on the notion of doing a series called SPIDERMAN, but it seems more likely that Kirby was the one who pitched the idea to Lee.

Tom Brevoort, “Lee & Kirby & Simon & Ditko & Oleck: The Spider and the Fly”

These pages have never been made public but we have enough eye-witness corroboration to know it existed in fact. Steve Ditko had seen them and described it. Jim Shooter, Marvel Editor in Chief in the 1980s also claimed to have seen these pages [2]. It’s not known if these pages currently exist in Marvel’s internal archives. Kirby’s Spiderman was a more heavyset character closer to Captain America in appearance, or a football linesman. He had a web-gun much like The Fly. Kirby’s pitch had the hero stay with his Aunt and Uncle, but the Uncle was a retired police captain.

According to Steve Ditko,

“For me, the Spider-Man saga began when Stan called me into his office and told me I would be inking Jack Kirby’s pencils on a new Marvel hero, Spiderman. I still don’t know whose idea was Spiderman.”

Steve Ditko, Strange and Stranger, Page 53 [3]

Ditko also elaborated on the difference between Kirby’s concept and his:

The uncle, according to Ditko, was “a retired police captain, hard, gruff, the General Thunderbolt Ross type (from the Hulk series) and he was down on the teenager…The only connection to the spider theme was the name.”

Steve Ditko, qtd. by Blake Bell, Strange and Stranger, Page 53 [3]

So Ditko gives some idea of what Kirby’s original concept was like. At some point, the decision was made (it’s not definitely known by whom) for Kirby to step back and allow Ditko to develop the concept of Spider-Man. Let me say that the important thing to notice is that Kirby’s concept of Spiderman had the character as a “teenager” as Ditko identified it. The concept of the character as teenager was emphasized in the dynamic that Ditko identified with the Police Captain Uncle, who was “down on the teenager” which is definitely not the case with the warmhearted and paternal Uncle Ben of Amazing Fantasy #15.

[ASIDE: One can’t help but notice that the concept of a Police Captain as a paternal figure, which featured in the original pitch, seems to prefigure, consciously or subconsciously, the character of Captain George Stacy in the Lee-Romita run. Even then, George Stacy is a supportive ally of Spider-Man and not “down on the teenager” as it was in the Kirby pitch].

What is a fact is that someone — it might be Kirby or it might be Stan Lee — decided to make Spiderman a “teenager” and this was there before Steve Ditko stepped in. What led to that decision by Lee and Kirby? What could possibly have influenced their ideas of “teenager”?

ORIGIN STORY: THE TEENAGER

It’s important to emphasize at the outset that the concept and the word “teenager” was pretty new and recent in the late 1950s. Nowadays people assume that “teenager” is some constant and eternal fixed category. But in fact the concept of the teenager is extremely new and in a large sense it’s fabricated and made-up. It is not by any definition an eternal historical category, or an organic naturally occurring social distinction. A number of cultural historians pointed out that the concept of the teenager was invented in the 1940s, and specifically highlight a 1944 LIFE magazine issue as the source of all teenage wastelands:

“Historians and social critics differ on the specifics of the timeline, but most cultural observers agree that the strange and fascinating creature known as the American teenager — as we now understand the species — came into being sometime in the early 1940s. This is not to say that for millennia human beings had somehow passed from childhood to adulthood without enduring the squalls of adolescence. But the modern notion of the teen years as a recognized, quantifiable life stage, complete with its own fashions, behavior, vernacular and arcane rituals, simply did not exist until the post-Depression era…In its December 1944 feature, LIFE breathlessly discussed the “teen-age” phenomenon in language that, in 2013, somehow feels naive, chauvinistic, celebratory and insightful, all at once. That so many of the article’s impossibly broad, sweeping claims (“Some 6,000,000 U.S. teen-age girls live in a world all their own: a lovely, gay, enthusiastic, funny and blissful society. . . .”) clearly apply to a specific type of teenager — i.e., white, middle-class — tends to blunt some of the more incisive observations. But taken as a whole, the LIFE article and Leen’s photographs constitute a fascinating, early look at a segment of the American populace that, over the ensuing decades, for better and for worse, has assumed an increasingly central role in the shaping of Western culture.”

Ben Cosgrove, “The Invention of Teenagers: LIFE and the Triumph of Youth Culture” [5].

As Cosgrove notes, the original sample of “teen-agers” profiled by LIFE were entirely girls which is pretty ironic when we consider how “teenage” has ultimately come to be defined as mainly a male demographic. Cosgrove also identifies, correctly, that despite boasting a sample of 6 million “teen-age” girls, the reality is that LIFE presumed and took for normal the life and experiences of white middle-class Americans rather than a diverse and representative sample. Which is to say that the idea of teenage life as being idyllic and fantastic as LIFE defined “teen-age” (and which we still understand teenage life to be to some extent) obviously did not correspond to the reality of the majority of young people of the 1940s.

From the very beginning in fact we can see that there’s a drive towards seeing “teenage life” almost apart from, or independent from, considerations of class and race. This divide, between seeing a character as “teenage” as opposed to belonging to a specific class (and race), will be something of a recurring theme for the rest of this article. To return to the 1940s, even if the LIFE magazine described or sensationalized the concept of a nascent teenage sensibility, that would of course not be the same as claiming it did not exist. A tendency to sensationalize any trivial story as the next big thing ever is not the same as making something out of nothing. So let’s say, that LIFE is right, that there is a new sensibility and culture called “teenager” that emerged in 1944; would that, for all its class and race limitations, still be considered representative of teenage life of the 1940s? One cannot say for certain, or at least I cannot say for certain given that I am indulging in amateur sociology and not the real thing. But I would say that when we consider “young person lifestyle” in the 1940s, one major elephant in the room that needs to be addressed is World War II.

It’s a fact that young people, many of whom we would identify as teenagers today, fought in World War II in large numbers. The minimum recruitment age for enlistment was 18 and there are documented instances of many young people lying about their ages to fight the war, with some as young as 14 and 15. By some measures, 200,000 underage recruits comprised the American fighting force [6]. Culturally, most World War II movies which center on the grizzled macho veteran old soldier tend to elide this fact.

For example, Captain America: The First Avenger aged up Bucky Barnes to be the same age as Steve Rogers because presumably contemporary audiences wouldn’t accept the fact that Kirby-Simon’s Bucky was a young boy sidekick tagging along Captain America, but in fact soldiers as young as Bucky absolutely did fight, die, and kill for their country in the war against fascism. So yes, Golden Age Kirby and Simon were far closer to reality than our contemporary edgelord reimaginings of the past. None of this is to give offense to Sebastian Stan or the MCU, merely to highlight that the casting and aging-up of Bucky is a reflection of 2010s era perceptions of the past. Like all era-specific aesthetic prejudices, it need not correspond to the actual history of the past.

It’s ironic that Bucky Barnes, originally portrayed and introduced as a teenager is now exclusively imagined or retrofitted as an older figure. Whereas Peter Parker who aged far more in the Lee/Ditko run than Bucky did in Simon/Kirby, is increasingly and continuously shown as a teenager. In both cases this isn’t driven by realism but by entirely subjective perceptions and assumptions people have about the past.

The fact that a significant chunk of America’s fighting men were young is also a significant fact in the history of comics. Comic Books saw their sales rise to great heights during World War II. A fact highlighted in an episode by the YouTube channel ComicTropes [7]. In general, this was the period when comics readership was high across the board, as ComicTropes points out (around timestamp 10:30mns) that more than half of America’s population was reading comics (either in newspapers or in cheap books). Still the popularity of comics among serviceman is a widely documented observance. It’s something even Military websites, in a way of trying to prove they are hip like to emphasize [8]

All this is to drive home the wide-gap between “the perception” of teenage life and “the realities” of teenage life even in the 1940s, the decade when the word was coined.

It’s important to emphasize this cultural context, to comprehend the fact that Spider-Man’s four main generative figures — Joe Simon (1913-2011) Jack Kirby (1917-1994) Stan Lee (1922-2018), Steve Ditko (1927-2018) — were all Pre-Depression in their births, and in the case of all except Ditko, Pre-Depression in their adolescents.

When Kirby, Lee, Simon, and even Ditko, were teenagers — nobody called them teenagers.

The concept of Spider-Man as a teenager pre-existed Ditko’s involvement with the title per his own admission and description of Kirby’s Uncle being “down on the teenager” which signifies that Kirby’s Peter was teenage. The decision of making Spider-Man a teenager was never Ditko’s. Indeed among the aspects of Spider-Man that we can definitely argue are Ditko’s contribution is the decision to age up the character.

ORIGIN STORY: TEENAGERS IN COMICS BEFORE SPIDER-MAN

Peter Parker is not in fact the first teenage superhero, nor is he the first young person as a superhero, nor is the first non-sidekick young solo superhero i.e. the first instance of a character-type normally relegated to sidekick status promoted as lead superhero in its own right.

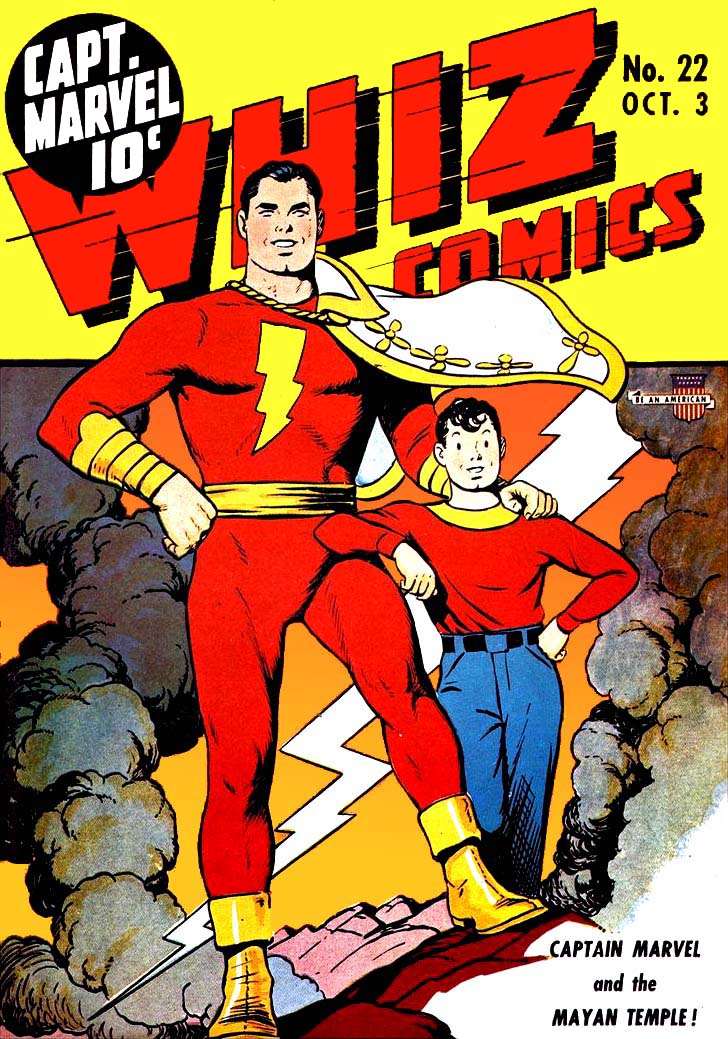

In all of this he was preceded by Fawcett Comics’ Captain Marvel/Billy Batson.

Captain Marvel as developed originally had an alter-ego of a small child called Billy Batson who when he uttered the magic word Shazam (today the actual brand name of the comic) transformed into an adult superhero. In the 1940s, Captain Marvel outsold Superman and was the #1 Superhero in the industry [9]. In a time of boy-sidekicks like Robin the Boy Wonder as well as Bucky Barnes, Billy Batson got to be a child who was also the protagonist and lead character of his own comics. So in a large sense Spider-Man‘s glory was achieved in the 1940s and in the 1940s, the majority of young readership especially during the war, flocked to Captain Marvel over Superman. Captain Marvel was “the superhero that could be you”, and relatable to many young people in their war effort against fascism. It’s only because of a lawsuit by DC that the character has fallen into obscurity. Had Captain Marvel remained in print and maintained by corporate overlords less indifferent and incompetent than Fawcett Comics, it’s likely the character wouldn’t have been memory-holed by the time of Spider-Man’s debut.

Captain Marvel became so big that he developed his own Marvel Family of superheroes including Mary Marvel (the prototype for Supergirl) and crucially for this discussion, his own sidekick — Captain Marvel Jr./Freddie Freeman. Despite being a sidekick to a boy-hero, and absolutely forgotten today, it’s Freddie Freeman who yielded the biggest cultural influence of any Golden Age superhero. Freeman/Captain Marvel Jr. was so big and famous in the 1950s that he had his own comics and unlike Billy Batson who transformed from boy to man, Marvel/Freddie remained a teenager when he transformed.

Captain Marvel Jr. had his own line of comics that ran for several issues and crucially, these comics became a touchstone for Elvis Presley [10].

“Elvis used comics as an escape… Around the age of 12, Elvis discovered Captain Marvel Jr. and quickly became almost obsessed with him.” Billy Smith, longtime Elvis friend, said that Elvis admired the dual image of Captain Marvel Jr. — normal everyday guy and super crime-fighter. The everyday guy is poor teenager Freddy Freeman, the alter ego who turned into Captain Marvel Jr. when he spoke the magic words.The author takes this one step farther. He says, “This is why Elvis idolized Cap Jr. – because the Freddy Freeman/Captain Marvel Jr. character was a perfect mirror image of the once and future Elvis. Freddy represented Elvis as he was, and Captain Marvel Jr. represented Elvis as he wished to be.”

ElvisBlog, “Elvis and Captain Marvel Jr.”

The first big superstar of rock and roll, and certainly one of the original teenage hearthrobs was a comics nerd and the comics he held a torch for was Captain Marvel Jr. and not any of the Robins, Batmans, Lanterns, Flashes, leave alone Supermans. Elvis modeled his hairstyle on Freddie Freeman and in various concerns took to wearing the blue-suit and cape ensemble of Freddie to better resemble his hero. So yeah, Elvis was the first cosplayer and a good part of the modern rockstar stage aesthetic comes from superhero designs in general, and Freddie Freeman in particular. Elvis Presley’s reading and identification with Freddie is also identical to what several writers and commentators have long claimed was the core appeal of Spider-Man i.e. his youth and relatable nature.

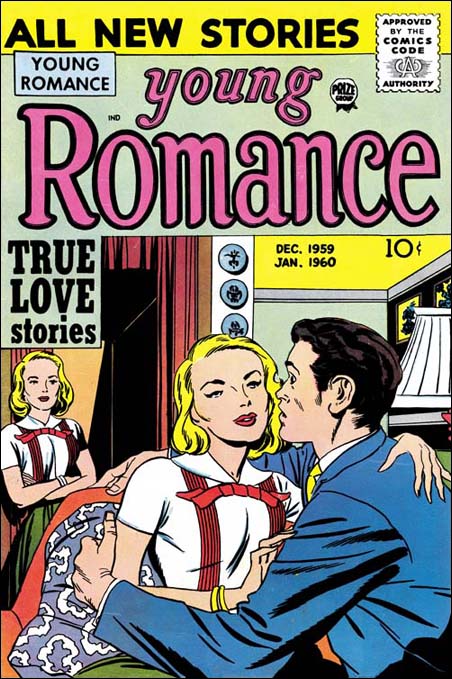

Since the 1950s was the last time non-superhero comics commanded the mainstream, it’s also important to highlight Archie. John Romita Sr. worked on Archie and romance comics inspired by Archie before coming over to Spider-Man and certainly the Peter/Gwen/MJ love-triangle in comics owes its configuration to Betty and Veronica at least in the early issues. Archie dating to 1941 and developing slowly and surely after that certainly captured and defined a teenage perspective in the post-war era especially in a time when young children tended to read Harvey Comics characters like Richie Rich, Casper the Friendly Ghost, Little Lulu among others, which had child protagonists and adventure/fantasy stories. Compared to the others, Archie, for all its flaws and dubious values (which even in the 1950s provoked ire, see Harvey Kurtzman’s hilarious satire: “Starchie!” in MAD Magazine), was closer to reality, dealing with situations that were familiar to the kinds that resembled real-life high schoolers even if none of the characters qualify as realistic representations in any sense.

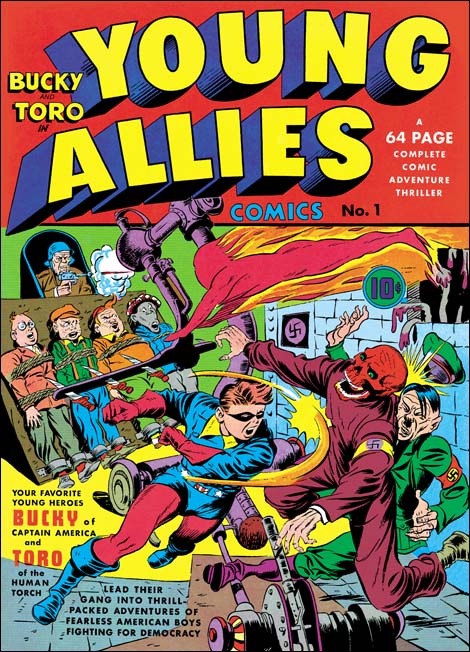

Jack Kirby who sat with the concept of Spiderman for a near-decade before arriving at Marvel was an industry veteran (and also an actual legit World War II veteran who fought and killed Nazis) who embraced changing tastes of readership. In the 1940s, he and Joe Simon launched the groundbreaking Young Romance series which invented the romance comics of the ’40s and ’50s, in turn greatly influencing the direction of Archie Comics as it developed further, and likewise spawning many imitations including from Stan Lee at Timely Comics at the time [11].

Young Romance hit newsstands in the summer of 1947, with the tagline “Designed For the More ADULT Readers of Comics” to set it apart from its younger skewing peers. Although relatively tame by modern standards, Young Romance’s stories featured sultry love triangles, brooding heroes, troubled relationships and plenty of drama. The comic was an instant hit, selling millions of copies, and Crestwood quickly asked the pair to work on a second romance series, Young Love. By the time Crestwood published Young Love in 1949, the newsstand was flooded with dozens of imitations, including comics by publishers like Atlas (Timely Comics’ successor), Charlton and Fawcett Comics.

“Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, and the Dawn of the Romance Comics”

When he and Joe Simon were developing Spiderman, they initially retooled the concept into a character called the The Fly. The Fly was an imitation of Captain Marvel. Its protagonist Tommy Troy was a child who transformed into The Fly by rubbing a magic ring.

This proves that Chris Sims was right when he talked about the depiction of young people in comics before Spider-Man:

Now, just to cover the bases, here’s another obvious point: Spider-Man wasn’t the first “teenage” character in superhero comics. There are kid sidekicks almost from the start that certainly fit the bill, and while it’s easy to argue that the distinction was that Spider-Man was a lead character in his own right, which is certainly a big factor in what sets him apart, Robin was headlining solo stories in the Golden Age. The difference wasn’t just that they were sidekicks, it’s that they were kid sidekicks. They were children…it’s worth noting that DC almost managed to get there first in 1958, when Otto Binder and Al Plastino introduce the Legion of Super-Heroes. It’s an entire team of teenage characters that, because of their isolation from the rest of the DC Universe, would eventually evolve into something that feels fittingly ahead of its time in terms of crafting those soap operatic relationships and adventures that you’d get from later, post-Marvel books. At the time, though, it was just a little too early to really capture it, and the Legion starts off reading pretty clearly as “children” rather than “teens.” Which, to be fair, is actually what I like about them — a team of superheroes who are complete jerks because they operate on the completely accurate logic of children who have formed a club to exclude others.

Chris Sims [12]

Which is to say that writers of superhero comics in the 1940s and 1950s didn’t quite have an handle on adolescence and their idea of “young” characters was to write stories that were far more childish and far more prepubescent. This was reflected even in Archie Comics which as noted by Sims, though featuring teenage life, skewed even younger, and are fantasies about teenage life meant for an audience of kids.

Archie is clearly a teenager from the beginning, but the stories themselves are directed at kids, and use a bunch of awkward phrasing…to get that idea across. Even once they get the term and start referring to him as “America’s Typical Teenager” — which, let’s be real here, is possibly the worst tagline of all time — the stories are very clearly for kids.

Chris Sims [12]

In other words, Jack Kirby wasn’t quite well-equipped to portray teenage life, hence Ditko’s observation that Kirby’s original story with the police captain Uncle “down on the teenager” had a patronizing quality that Ditko had to remove in order to properly pitch and update things. When Kirby developed Fantastic Four, he conceived of the dynamic between Johnny Storm and The Thing, with Johnny being the angsty kid and Ben Grimm (widely seen as the character closest to Kirby himself) as the crusty old working-class senior who finds him exhausting. It’s plausible to infer that Kirby’s original concept for Spiderman simply had the Police Captain Uncle and Spiderman as a variation on Grimm and Torch.

From a generational perspective, Jack Kirby distilled and handed down to Steve Ditko in his concept, the pre-war understanding of a young hero. A young character, modeled on Billy Batson (the most dominant superhero of his age), and as the 1950s waned, a teenager who got angry at his senior. Kirby was a parent to four children, and his eldest daughter Susan (who like Benjamin Kurtzberg, Kirby’s Dad, shares a name with one of the Fantastic Four) born in 1945 became a teenager in the late 1950s and so provided him with first-hand reference of teenage culture and perhaps as a way to ventriloquize his own sense of generational divide and being out of touch with kids these days.

Kirby’s influence perhaps even stretched to the name of Spider-Man’s secret identity. We don’t know whether Kirby’s original concept had character names but it’s a fact that in 1955, Kirby wrote and drew a Golf comic called “On the Green with Peter Parr” [13]. It’s not outside the realm of possibility that Kirby reused that name for his Marvel Spiderman pitch, while adding a K.

Stan Lee often claimed he preferred “alliterative names” because he had a terrible memory [14]. It’s still possible that the name of Peter Parker was entirely Stan Lee’s and there’s evidence that he named other Marvel characters. At the same time the concept of heroes having alliterative names goes back to Superman and Clark Kent which is a sound alliteration admittedly. And in fact heroes having alliterative names was de riguer – Billy Batson/Captain Marvel, Freddie Freeman/Capt Marvel Jr. Simon-Kirby’s character The Fly had Tommy Troy. And of course you have Archie Andrews and Richie Rich outside superhero comics in the same period (to say nothing of characters like Donald Duck and Gladstone Gander who were prominent parts of Carl Barks’ immensely popular and influential comics of the 1950s). So it’s more than a little possible that the name of Peter Parker evolved from Kirby’s wilderness years and was suggested and proferred in the original pitch (which makes no mention if character names were present).

ORIGIN STORY: STEVE DITKO IN HIGH SCHOOL

Both of Spider-Man’s two acknowledged creators, Stan Lee and Steve Ditko, attended high school, both of which was shaped and altered by different circumstances and different generations. Stan Lee was born in 1922 and he went to high school in the mid to late 1930s during the height of the Great Depression. Lee attended the DeWitt Clinton High School in the Bronx (Batman co-creators Bill Finger and Bob Kane were alumni, as was Will Eisner though Lee appeared to have no contact or interactions with them). While studying at school, Stan Lee was driven to work several odd jobs to help support his parents, similar in part to Peter’s drive to provide for his Aunt May [15].

In contrast to all these jobs, school held little interest for Stan. “I didn’t hate being in school,” he would later tell an interviewer, “but I just kept wishing it was over and I could get into the real world.”

Abraham Riesman, True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee, Page 21, 22, Chapter 1.

Steve Ditko was born in 1927 and he entered high school in the late 30s through the early 1940s at the Greater Johnstown High School in Johnston, Pennsylvania.

More than a few commentators have pointed out the startling similarity between Ditko’s photograph on the High School Yearbook in his Senior Year and Ditko’s drawing of Peter Parker [16].

Ditko seems to have modeled Peter Parker’s high school in Midtown Manhattan on his own Pennsylvania High School and it’s easy to presume that Ditko modeled the high school Peter on his own high school experiences [16]. High School at Johnstown certainly did inspire, as it perhaps did to Stan Lee, his sense of class difference and exclusion.

“Johnstown’s two-tiered economic class structure was reflected in its school system. Regardless of their scholastic aptitude, children of the wealthier class were tracked into academia, while the working class was dispatced into vocational training. Stan Lee, Spider-Man’s co-creator and scripter, had Peter Parker growing up in Forest Hills, New York, but the high school Ditko illustrated was his from Johnstown, with the same little crenellated battlements at the top. The character of Flash Thompson existed in Ditko’s shop class – the bully, beating up other kids for their lunch money.”

Blake Bell. Strange and Stranger. Page 15 [16].

Ditko loved comics from an early age and he aspired to be an illustrator and cartoonist from a young age though his parents felt this career was impractical and probably not lucrative. In terms of class, Ditko was directed to a vocational track which meant that he graduated high school with little sense of “academic placement” as we call it today. This fact is reflected in his yearbook where it’s mentioned: “STEPHEN J. DITKO – “Steve.” Vocational Course Ambition: Undecided” [16]. Ditko wished to work on comics for a living but it wasn’t the kind of thing one announced in the 1940s and Ditko’s parents had doubts about the possibilities of such a career.

After high school, Ditko enlisted in the US Army and served a tour of duty for several years before enrolling in the the Cartoonists and Illustrators School (later the School of the Visual Arts) in New York City in the year 1950. Ditko was able to attend this School thanks to the GI Bill. There he studied under The Joker’s co-creator Jerry Robinson and he was remarked to be a talented and capable student [17]. It was Robinson who recommended Ditko work with Stan Lee, then editor of Timely Comics who visited the school scouting for talent. Ditko also worked at Simon and Kirby Studios and other small comics publications during the late-50s.

INTERLUDE: THE GI BILL CREATED SPIDER-MAN

Given Ditko’s latter-day Randian turn, it’s worth making a few observations. Ayn Rand was an author turned self-proclaimed philosopher (recognized by no philosophy department in any major academic institution) who opposed government investment and favored unchecked free-market capitalism. In real-life Rand eventually came to depend on social security and medicare after opposing such programs for most of her life, and this without recanting/modifying/qualifying her views [18]. In the same manner, Steve Ditko’s career and as such the success and triumph of Spider-Man owes itself primarily to the G. I. Bill of Rights which provided “academic assistance to veterans” opening higher education and better vocational access to people from a working-class [19].

As Gore Vidal remarked, in an otherwise controversial interview from 2009, “That policy [GI Bill] changed the whole class system in the United States. Before it, you had to be a doctor’s son to go to college. After that bill, everybody could go.” [20] Of course, not everybody. As Ta-Nehisi Coates argued in his celebrated “The Case for Reparations”, the GI Bill for all its social-democratic positive good, ultimately was enforced in a manner that excluded African-Americans and is one of many policies that benefited the white-working class at the expense of African-American and Non-white poor [21]. These seemingly extraneous details is important because as much as we contextualize Spider-Man in terms of teenage life and class relations of the early 20th Century, it’s important not to get too carried away and pretend that Spider-Man as a character and IP is in any way “innocent” of larger historical issues with representation.

The fact that a working-class Slovakian immigrant (second generation) like Ditko benefited from a government program that directly led to him working with the very people (Simon, Kirby, Lee) who provided him the concept of Spiderman, when that same program was denied to many African-American veterans (some of whom faced direct action in combat unlike Ditko) is a fine example of the ways white privilege and entitlement have always been the true “invisible hand” of American capitalism. In the face of this reality, the successes of Ayn Rand as an author and the embrace of Rand by both Stan Lee and Steve Ditko is profoundly hypocritical and an act of deep historical denial.

Ayn Rand was a popular author during the 1940s and 1950s and Stan Lee himself was a big admirer of Rand, and it was Stan who introduced and recommended her books to Ditko [22]. Considering the size of Ayn Rand’s books and Ditko’s workload, we can presume that he took his time familiarizing with her works and that Ditko’s Randian turn was gradual. As such we must discount retrofitting the later objectivist Ditko on to the young artist who started working at Timely and who began working on Spider-Man.

Still the Rand connection professed by Ditko is important to contextualize and rebut pre-emptively so as to prevent a too rosy and uncritical identification of Ditko as ‘an artist of the common people’ or as a working-class artist. He was that to some extent but ultimately not the kind to pay it forward. It’s also an example of the complex ways race and class at various levels had to be excluded before one even considered the category of “the teenager”. Such complex institutional and social factors I mention above were rarely represented from most discussions of teenage life in the 1940s and 1950s and were absent from Archie Comics to say the least.

ORIGIN STORY: DITKO (contd).

As such the character of Spider-Man/Peter Parker in so far as he represents a working-class scholarship boy who goes to college on his grades and independent knowhow, while certainly charming and appealing as an adventure story is the kind of narrative that in cultural-historical and class terms was only ever conceivable as a result of US social-welfare policies. Before, one had to imagine a peasant superhero in the mold of Freddie Freeman or Billy Batson, and derive powers from genies and wizards.

At the time Ditko wrote and drew Spider-Man in 1962 he was 35 years old and had developed a receding hairline which he was quite honest about representing warts and all in the pages of Spider-Man in the backup sketch at the end of Amazing Spider-Man Annual 01 (also known as “The Sinister Six”).

So Spider-Man is not exactly a contemporary creation of a teenager. To the extent Peter Parker bears a physical resemblance to Steve Ditko, it would be mainly a projection of Ditko’s high school years, and an idealization of his teenage self who had a full head of hair as per the Yearbook photograph. The fact that Peter graduates high school and goes to college on a scholarship can be seen, in some sense, as a wish-fulfillment on Ditko’s part given that at the time he graduated in 1945 he had no options (Marked for “Vocation” and “Undecided” in his Yearbook). Had it not been for his enlistment, given the GI Bill of which he was a beneficiary, Ditko would likely never have worked in comics and Spider-Man wouldn’t exist in the current form. And while the benefits ought to have been more equally distributed, Ditko did deserve a share of the GI Bill all things considered.

Ditko’s high school and teenage years coincided with World War II. He graduated high school in 1945 and immediately enlisted into the US Military in 1945 right after he graduated. 1945 of course was the year when the war ended and so Ditko didn’t see active frontline service (unlike Jack Kirby). Rather he served as a soldier stationed in Occupied Germany, where he drew his first cartoons for an Army newspaper. In his life, Ditko was famously reclusive but after his passing in 2018, the Ditko Estate has slowly allowed comics scholars a peek and glimpse into his life, including sharing images of Ditko’s years in Army Service [23].

Ditko occupies a strange in-between place. He belonged simultaneously to both the ‘Greatest Generation’ and the ‘Silent Generation’. As a teenager, he accepted military service and enlistment as a given but at the same time he had the fortune to spend much of the war years state-side in high school and got to graduate which meant that he was uniquely positioned, biographically to reflect both Pre-War and Post-War conceptions of youth and teenage life.

Simon, Kirby, Lee, and Ditko all grew up Pre-World War II and either witnessed or experienced the struggles the Depression, or World War II, and their teenage, adolescence and early adult years (20s in the case of Jack Kirby) were defined by rapid changes, convulsions and poverty. As such, none of Spider-Man’s creators were really in a position to speak from any real first-hand experience of “teenage life” as it was defined by the 1944 LIFE profile. Such a concept would have struck them as alien and deeply entitled. Given their working-class origins, their freelance years of struggle, their period of enlistment, the concept of “teenage life” would have seemed to them to be fundamentally unrepresentative to the majority of young people’s experiences in the 1940s.

It’s also worth mentioning that of Steve Ditko’s major creations in Marvel, it seems that Doctor Strange was more personal to Ditko than Spider-Man [24]. Spider-Man was at heart, a Simon-Kirby dead-end concept that Ditko salvaged and finally set in motion, whereas Doctor Strange was a concept entirely generated and developed by Ditko himself. As Bell observes, Ditko seemed to have put far more effort into Strange Tales #146 his final Doctor Strange story than on Amazing Spider-Man #38. Furthermore a visitor at Ditko’s studio reported that Ditko had pencilled two Strange stories without pay:

“Ditko never explained why he would bother to pencil two complete stories that would remain as unpaid work…Whatever the case, Strange Tales #146 was an effective last gasp, documenting Dormammau’s thrilling cataclysmic plunge right into the heart of Eternity. Ditko’s last issue of Spider-Man (#38) was anti-climactic by comparison, which confirms Ditko’s soft spot for his Master of the Mystic Arts. As John Romita concludes, “I think the biggest thing we miss was he didn’t continue on Dr. Strange. No one could do Dr. Strange like him…That’s the one I miss the most.”

Blake Bell, Strange and Stranger, Page 79

Stan Lee in the 1960s never denied that Strange “Twas Steve’s idea” [25]. Stan Lee is credited for naming the character Stephen Strange, most likely in reference to Strange’s true creator, whose full name is Stephen John Ditko [26].

SPIDER-MAN WAS NEVER A REALISTIC TEENAGER

In 1962, when Ditko received Spiderman from Kirby, the character was already preset as a teenager, having originally been a young child like Billy Batson. Ditko wasn’t really in a position, nor was he equipped to represent, teenage life of the 1950s and early 1960s. His memories of high school was in a time before the concept of the teenager and for him graduation led to military service and away from his peers who participated and engaged in building the post-war consumer society.

In other words, Spider-Man in 1962 wasn’t a realistic portrayal of teenage life in the early 60s in New York. Ditko’s high school was in Philadelphia and he used a Philadelphia high school from the 1940s as a model for a Manhattan high school in the early 60s. So the conception of Spider-Man as a teenager would have been more than a little alien to Ditko in particular and as such Spider-Man as a character was developed on more universal lines than anything pertaining to real living teenage life of the 1950s and the 1960s.

If anything it’s likely that Ditko’s lack of familiarity with teenage life of the post-war era influenced his characterization of Peter Parker. Peter as a character seems to be dressed in more out-of-fashion clothes than his teen contemporaries. Flash and Liz and others wear clothes similar to the cast of Archie while Peter dresses in a more old-fashioned and formal get-up as a high school student.

Ditko might have used Archie Comics and Romance Comics as a referent for teenage life as well as movies and magazines (he was known for stacking his studios with reference material with images for anything he could use in his comics) to simulate a general look at high school while also using Peter’s status as a bullied outsider to reflect his generation gap. The divide between his experiences as a teenager in the 1940s and the 1950s, found a mirror in Peter’s sense of aloofness from the crowd, his need to work for a living and get out in the real-world which would likewise have engaged Stan Lee since it reflected his own high school years during the Great Depression. So in Spider-Man, in 1962 you have a character who reflects a 1940s teenage experience, surrounded by teenage stock characters from 1950s comics.

So in a certain respect, Spider-Man is anomalous not archetypal. His stories neither featured nor represented the assorted tropes with teenage life as it came to be defined in the post-war era nor were Lee or Ditko sufficiently plugged in with teenage life in their early years to make the portrayal of high school or social life truly representative of the emerging teen culture. Which is to say that the success of Spider-Man comes because the character’s conception came at a crossroads of generational markers and competing generational memories. We can see this in Peter’s relations with his Aunt May who given her exaggerated age and features feels like a survivor of the Great Depression (which originally she was given that Peter was absolutely a contemporary of 1962, which meant that May and Ben were Greatest Generation survivors who spent their youth during the Depression).

The idea of Peter Parker as a poor kid working to support his elderly parents hearkens to the Depression years especially when we consider multiple panels in the Lee-Ditko run which shows Peter fantasizing about his Aunt May reduced to destitution, and below the poverty line should he fail to support her. The image of May in this panel from a fantasy sequence in ASM#04 certainly evokes some of the stark experiences of poverty in the Great Depression as attested in the photographs of Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange, or in the figure of Ma Joad in The Grapes of Wrath, the stern, firm but loving matriarch of a family reduced to strife during the Dust Bowl. Steve Ditko is reported to have been close to his family, stayed in touch with them, and despite his busy workload always returned home for family dinners and was close to his brothers and nephews [27]. Stan Lee by contrast had far more distant and strained relation with his father and brother, but on the other hand was rather devoted to his wife [28].

This layering of generational contrasts, and clashing biographical details, explains in part Spider-Man’s universal appeal and his true originality and endurance because teenage life in the 1960s rapidly evolved from the 1950s with the arrival of The Beatles (referred to in ASM#14) and later the counter-culture and Civil Rights Movement. This new teenage paradigm made Archie comics with its vapid and shallow consumerism of the 1950s feel especially irrelevant, given its disengagement from the reality of its time (the lack of any African-American characters in all-white Riverdale in the 1950s is very much a Pre-Segregation Pre-Brown v. Board of Education view). Spider-Man‘s sense of being outside and essentially rejecting the crowd of Flash and Liz Allan in favor of living in the real world, i.e. working at the Bugle better captures the spectrum of youth of the 1960s than it would have if Ditko had been entirely enshrined in reproducing the perceptions of that era.

CONCLUSION

There is much that’s taken for granted in the assumptions behind the successes of Spider-Man as a character. In this article, as in my previous in the Re-Examining Spider-Man series (Introduction, 01, 02), I have done my best in pointing out all that is left out in presuming that Spider-Man was inevitably a teenage superhero or inevitably a superhero that would succeed on account of him reflecting real-life teenage experiences. Little of this is evident. None of this of course changes the universal appeal of Spider-Man as a character. This universality, the ability of Spider-Man to speak to different kinds of audiences and different experiences, the versatility of the character is closer to the reasons for the character’s success.

The real question to ask is about the character’s longevity. Why is it that Spider-Man remained popular and relevant in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s and beyond when Freddie Freeman/Captain Marvel Jr faded away despite having the world’s most famous singer as his #1 fanboy? One can point out that Spider-Man as a character changed and grew as I would prefer to certainly. However, it can also be pointed out that Archie Comics somehow still remains famous and in print despite remaining unchanged in most respects from how it was written in the 1940s and 1950s. One of the few non-superhero comics to be continuously in print and in demand from the Golden Age.

Ultimately success is a mystery. We speculate on the success and longevity of Spider-Man in the aftermath of the character’s longevity and success. In other words, Spider-Man is spoken of as an archetypal teenage superhero rather than Freddie Freeman because we like to retrofit assumptions and values backwards, putting the cart before the horse, rather than seeing the development and success of Spider-Man as an unlikely combination of Kirby/Simon/Lee/Ditko in the early 1960s USA.

Absent these people, absent that year, absent the country, absent the GI Bill — you have no Spider-Man.

REFERENCES

- “Lee & Kirby & Simon & Ditko & Oleck: The Spider and the Fly.” The Tom Brevoort Experience. October 24, 2020.

https://tombrevoort.com/2020/10/24/lee-kirby-simon-ditko-oleck-the-spider-and-the-fly/ - Jim Shooter. My Short Lived Inking Career.

http://jimshooter.com/2011/03/my-short-lived-inking-career.html/ - Blake Bell. Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko. Fantagraphic Books. 2008. Page 53.

- N/A

- “The Invention of Teenagers: LIFE and the Triumph of Youth Culture” Ben Cosgrove Time Magazine. September 28, 2013.

https://time.com/3639041/the-invention-of-teenagers-life-and-the-triumph-of-youth-culture/? - “Young Warriors: Some Veterans Lied About Their Ages”

https://abcnews.go.com/GMA/story?id=3850523&page=1 - ComicTropes

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FzT9I-9N5c4&t=2s - “This is Why WWII Troops Are to Thank for the Rise of Comics”.

https://www.military.com/undertheradar/2018/10/19/why-wwii-troops-are-thank-rise-comics.html - “Reclaiming History: Superman Vs. Captain Marvel” The Comics Cube.

http://www.comicscube.com/2011/08/reclaiming-history-superman-vs-captain.html - “Elvis and Captain Marvel. Jr”. ElvisBlog.

https://www.elvisblog.net/2005/11/20/elvis-and-captain-marvel-jr/ - “Jack Kirby, Joe Simon, and the Dawn of the Romance Comic”

https://comicbook.com/marvel/news/jack-kirby-joe-simon-and-the-dawn-of-the-romance-comic/ - Chris Sims. Ask Chris #206.

https://comicsalliance.com/ask-chris-206-spider-man-and-the-rise-of-the-teenage-superhero/ - “On the Green With Peter Parr” The Jack Kirby Reader.

https://www.comics.org/issue/770866/ - “Stan Lee Only Gave Heroes Alliterative Names So He Could Remember Them”

https://screenrant.com/stan-lee-alliterative-names-bad-memory/ - True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee. Abraham Riesman. Published in 2021. Page 21-22, Chapter 1 (online edition).

- Blake Bell. Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko. Fantagraphic Books. 2008. Pages 14-15.

- An Interview With Jerry Robinson – The Creator of The Joker March 07, 2018. https://www.nerdteam30.com/creator-conversations-retro/an-interview-with-jerry-robinson-the-creator-of-the-joker

- “When Ayn Rand Collected Social Security & Medicare” Open Culture.

https://www.openculture.com/2016/12/when-ayn-rand-collected-social-security-medicare.html - Blake Bell. Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko. Fantagraphic Books. 2008. Page 16.

- “A Conversation with Gore Vidal”. The Atlantic. October 2009.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2009/10/a-conversation-with-gore-vidal/307767/ - “The Case for Reparations”. Ta-Nehisi Coates. The Atlantic. June 2014.

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2014/06/the-case-for-reparations/361631/ - Blake Bell. Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko. Fantagraphic Books. 2008. Page 86.

- Robert Elder. The Comics Journal. March 16, 2021.

http://www.tcj.com/beyond-spider-man-steve-ditkos-letters-provide-insight-into-an-enigmatic-creator/ - Blake Bell. Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko. Fantagraphic Books. 2008. Page 79

- “1963 Stan Lee Letter to Fan Reveals Doctor Strange’s Original Name”. Syfy Wire. December 12.

https://www.syfy.com/syfywire/1963_stan_lee_letter_to_f - “Who contributed more to Dr Strange dialogue?” J David Spurlock 19 October 2016.

https://zak-site.com/MarvelMethodArchive/141.html - Blake Bell. Strange and Stranger: The World of Steve Ditko. Fantagraphic Books. 2008. Page 16

- True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee. Abraham Riesman. Published in 2021. Page 73-76 (Print).

A very interesting and well researched article. I enjoyed reading it a lot.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you. Glad you liked it.

LikeLike